Click here to purchase the Ketogenic Backpacking cookbook on Amazon

Planning and Packing for the Appalachian Trail

The air was earthy and fresh. Our evening was illuminated by the exotic guest of light from the other side of the earth. Having bounced off the moon, it dropped to the fluffy bed of clouds below us and bounded up again, catching the fresh dew on the grass and tickling the pale lichen on the oaks. We were in a gallery of magician’s mirrors and an amphitheater of the heavens. Sitting atop Mt Tamalpais, the golden tresses of the hills known as the “seven sisters” undulated in the cool ocean breeze below us. We were alive. We were in love with one another and the outdoors. The world was our playground. I asked her to be marry me.

Four years, and many adventures later, we were two tiny specks picking our way through the glacier-carved, boulder-strewn expanse of California’s Desolation Wilderness. The question of backpacking food was forefront in my mind. Jess was four months pregnant with our first child. Long before this child was conceived, we had planned our first family adventure. The destination and scope of the adventure would be determined by the season in which our child would be born and the vigor of mother and child.

Our daughter Zia was due in late January, she would be 10 weeks old in mid-April, too late for a New Zealand trek, too early for any mountains in the west, but just right for starting the Appalachian trail.

By any modern standard, the fact that Jess would be contemplating a long-distance hike at 10 weeks post-partum was heroic. Uncertain of how her body would handle the rigors of the trail, we wanted to keep her pack as light as possible. This meant I would be carrying most of the load.

Bringing a baby meant carrying a little more weight. Zia herself would weigh 13lbs when we started and 16lbs by the time we finished our hike two months later. We had chosen a larger heavier shelter and exchanged our shared down quilt for separate sleeping bags, so I wouldn’t be woken every time Zia needed to nurse. With these changes and a few diapers (less thanks to Elimination Communication techniques) and warm clothes for the family our total family base weight was 49lbs including Zia1,2. Add another four pounds to keep two liters of water on hand to ensure Jess stayed sufficiently hydrated to produce a steady supply of milk for our growing adventurer and the total family pack weight was now 53lbs.

Split among the two of us, an individual weight of ~27lbs wasn’t bad, but we wouldn’t be dividing the weight evenly. Not having had the opportunity to carry our growing child for 10 months of pregnancy, I supposed this was my chance to pitch in. If Jess carried Zia and the water, my pack would be 46lbs… plus all the food.

Food would be the biggest part of our pack weight.

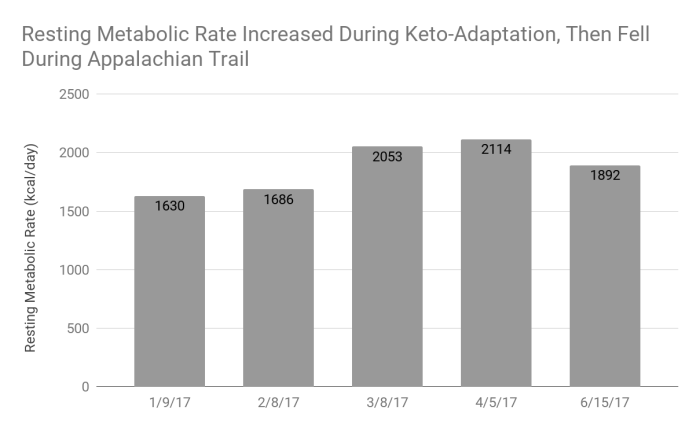

As we passed through the fragrant shade of a fir grove, Jess offered the classic biological strategy to an upcoming period of caloric deficit: “You could just get fat ahead of time and live off your fat stores” she said. Despite Jess’ breastfeeding we were both aware that mine would still be the biggest stomach to fill on the trail. At 190lbs and 8% body fat my caloric consumption while reclining on a lounge chair all day had been measured as 2114kcal at the DEXAfit lab in San Francisco. This value is known is the resting metabolic rate or RMR. The metabolic equivalent value for backpacking (metabolic equivalent, or MET, of 7) predicted an expenditure of 635kcal/hr. Multiply this by eight hours of backpacking and this added 5,080kcal to my daily caloric need for a total of 7,194kcal.

I knew from my recent DEXA scans at DEXAfit San Francisco, that I had 18lbs of fat on my body, 13lbs was essential which left me with 5lbs of fat to spare. For each pound of human fat, approximately 25% would be water and protein and 75% would be actual fat[1]3,4. At 9kcal/g this would give me 3000 kcal per pound of fat and a total of 15,000kcal. This was enough calories to supply two full days of hiking 8hrs a day.

Once this fat was gone, my body would only be left with my hard-earned muscle to burn. I could forestall this by fattening up ahead of time, a strategy my vanity made decidedly unattractive, not to mention the problem of hunger. But even with the extra fat stores, I was still at risk of losing muscle mass as some studies on caloric restriction in overweight individuals have shown.

As we squeezed under a huge sequoia lying across the trail, her pregnant belly now noticeably protruding, our thoughts turned to feeding Jess on our first family adventure.

Later Jessica’s post-partum breastfeeding RMR would be measured in the same DEXAfit San Francisco lab as mine at 1418kcal/day. The same 7 MET value predicted an additional 4,784kcal expenditure for eight hours a day of backpacking. This put her total daily caloric need at 6,202kcal and the total daily family caloric need at 13,396kcal. Although we were confident that our resting metabolic rates were accurate, we knew the expenditure during hiking would range greatly according to the terrain and pack weight, but one things seemed clear, we would need a lot of food.

On a typical diet of 30%fat, 15% protein and 65% carbohydrates, this 13,396kcal would consist of 447 grams of fat, 502 grams of protein and 2,177 grams of carbohydrate for a total weight of 6.9lbs per day. In reality, this food would be heavier thanks to packaging, water and fiber.

Just three days of the family’s food would bring my pack weight up to 74 pounds. Five days would of food would bring the pack weight up to an absurd 88lbs.

I knew the solution to fueling our family adventure was fat. I had experimented with the effect of the ketogenic diet on my cycling performance a year before and had excellent results. I had been looking for good ketogenic backpacking recipes but had found none. I would have to come up with them myself.

In the year leading up to our Appalachian trail hike, I experimented with ketogenic foods in the kitchen and on the trail. Each backpacking trip we went on was a test, there were a few delicious successes and many failed attempts to make mayonnaise on the trail without fresh eggs. As our child grew in the womb, so did my menu of ketogenic backpacking recipes.

I hope these recipes provide you with as much energy and enjoyment as they have provided me and my family.

Getting in Ketosis: Month One

I started the ketogenic diet three and a half months before hitting the trail to give me plenty of time to enter ketosis and test recipes along the way. I began recording my daily food intake using the MyFitnessPal app on February 5th, 2017, one week after my daughter was born.

At the same time, I began measuring my fasting morning levels of both types of ketone bodies. I used a blood drop from a finger prick to measure my blood beta-hydroxybutyrate levels using the Precision One-Touch Ultra and I exhaled into the Ketonix breath acetone monitor to measure my acetoacetate levels.

Once a month I visited the DEXAfit lab in San Francisco for a suite of measurements. This included 1) the gold standard of body composition, dual x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) which calculated the precise amount of bone, fat and a lean mass in my body; 2) infrared volume measurement of the circumferences of my arms, legs, torso and neck; 3) my resting metabolic rate; 4) and my respiratory exchange ratio (RER). This latter measurement revealed the extent to which I was burning fat vs carbohydrates at rest.

For three days I stayed on my normal mixed diet to establish a baseline. During these three days my average intake was 4093kcal, 51% fat, 35% carbs and 15% protein. This was a high fat diet averaging 229g of fat per day but not a low carb diet as it contained 362g of carbs. It was also a high protein and high fiber diet with an average of145g of protein and 102g of fiber per day. I had spent the prior four months on a diet restricted to ~2,700kcal/day with a similar nutrient ratio.

My average morning blood ketone levels after each of these three days was 0.2mmol/L and my breath acetone average was 71. Both values showed no significant ketone production.

On February 8th, 2017 I visited the DEXAfit lab. I weighed 191.2lbs, with 17.9lbs of fat, 161.1lbs of muscle and 8.0lbs of bone for a percent body fat of 9.6%. My resting metabolic rate was 1686kcal, this was substantially lower than measurements three months prior and was the result of having reduced my caloric intake to decrease my body fat for the last three months. My metabolism was burning 56% fat and 44% carbs at rest with a respiratory exchange ratio of 0.83.

After leaving the lab I began the ketogenic diet as follows: I restricted my carbohydrate intake to <20 grams per day, kept my protein intake <1g/lb of lean mass and ate as much fat as needed to feel full. On most days I had a ketogenic broth or other hot beverage on my morning hike carrying Zia, cheese and salami for lunch and tested out new recipes for dinner.

One month later, my blood ketone levels (BHOB) had crossed the 1mmol mark of nutritional ketosis only once. My average blood beta-hydroxybutyrate level for the month was 0.5mmol and my breath acetone level was 71. I felt fine, with none of the side effects of keto-adaptation others had mentioned such as fatigue, mental fogginess or light headedness but I wasn’t producing ketones.

My average intake for the month was 4,807kcal, 392g of fat, 17g of carbohydrate and 123grams of protein per day. I had eaten more than 20g of carbohydrate on only three occasions and on these days I had eaten 34, 21 and 28g. My protein intake had exceeded 161 only once at 167g on February 23rd, 2017. I had followed a ketogenic diet carefully, but I wasn’t producing ketones. What was wrong?

My body composition results were unrevealing, as I was nearly the same as before at 186lbs and 10% fat with 18.5lbs of fat, 158lbs of lean mass and 8.0lbs of bone. This 3.1lb drop in lean mass could easily be accounted for by the depletion of my glycogen stores on the ketogenic diet. The 0.6lb increase in my fat was all in my torso but very little of it in and around the organs. All in all, these changes were very small and could not reliable be distinguished from measurement variation.

My DEXAfit metabolic results after this first month, gave the clue as to what might have been happening. My resting metabolic rate had jumped up by 367kal to 2053kal and my % fat burning had decreased substantially down to 33% fat and 77% carbs with a respiratory exchange ratio of 0.93! How was I burning more carbs now that I was eating practically no carbohydrates (17g/day)? There was only one answer: gluconeogenesis.

My brain and body were relying on blood sugar produced in the liver by a process known as gluconeogenesis. I can’t be entirely sure where this glucose was coming from, but I suspect it was mostly from my dietary protein intake. Studies on fasting show that up to 20% of new glucose is made from the glycerol backbone of fats (triglycerides) during fasting and much of the remaining glucose is recycled from lactate via the fat-powered Cori cycle but it is still unclear what proportion of various substrates are used to provide glucose on a ketogenic diet37,171-174. My protein intake might have been high enough to keep liver glycogen and oxaloacetate levels sufficient to prevent the production of ketones and reduce my body’s fat burning. This drop in fat burning was a surprising result as the 1gram of protein/lb of lean mass calculation has resulted in nutritional ketosis for others20.

Getting into Ketosis: Month Two

In the following week I had two morning blood ketone reading of 1.1mmol but the rest were all 0.7mmol or less and my average for the week was 0.8mmol/L. At the same time, I was started taking blood ketone readings of Jess who was breastfeed but not eating a strict ketogenic diet and hers where through the roof at 1.3, 2.4 and 5mmol! She was eating the ketogenic backpacking recipes I was testing out in the evening as well as the hot beverages in the morning, but she was not restricting carbohydrates and was eating foods like chocolate, almond butter and rye seed toast.

Meanwhile my average daily intake for the last week had been 3606kcal, 351g of fat, 15g of carbohydrates and 96g of protein.

I was jealous. Was breastfeeding giving Jess a superpower to produce ketones? Why did my body prefer to make sugar from protein instead of producing ketones? After thinking it over for a week I decided to cut my protein intake from 161g (1g/lb of lean mass) to 72g starting March 15th, 2017. This amount was 10% above the 65g minimum protein intake for my body size recommended by the World Health Organization using their calculation of 0.36g/lb of total body mass. I had been hesitant to do this before because I was concerned that decreasing my protein intake would result in the loss of lean mass. This change took some recalibration of my diet and was especially tricky when trying to estimate the protein content of uncommon foods such as slow cooked Mangalitsa pork skin with adipose.

I started off with a day of only 33 grams of protein, mostly by accident because I didn’t tally my food until the end of the day, and I was afraid to eat too much protein. I was rewarded the next day with a fasted morning blood beta-hydroxybutyrate level of 1.4mmol/L. From that point on my levels were consistently above 1mmol and the average for the next two weeks was 1.2mmol/L with my highest reading at 5.7mmol/L!

After a week of consistently high readings I was confident I was in nutritional ketosis. In addition to my morning measurements I began measuring my blood ketone levels after specific meals to test the ketogenic effect of the recipes. I found I was able to slightly increase either my daily protein or carbohydrate intake so long as any given maintained a Wilder ratio over 3:1. My carbohydrate and protein intakes never exceeded 54 and 124grams respectively, and never this high in both on the same day.

Previously I had made the mistake of concentrating all my protein to one or two meals and apparently this had been enough to stimulate gluconeogenesis.

On April 5th, 2017, now at the end of the second month of the ketogenic diet and having finally produced ketones, I returned to DEXAfit San Francisco, excited to see the results.

My body composition results were potentially skewed by a side effect of the ketogenic diet: slowed intestinal transit time. As long as I can remember I have had a very rapid intestinal transit time and thus have been prone to diarrhea. In remember investigating this in college by eating sesame seeds with a meal as a tracer, then seeing them in my stool six hours later. The ketogenic diet had slowed me down to a normal pace and I went from several stools a day to once a day or even once every other day. Before each DEXA scan I fasted for 15hours overnight and had my scan at the same time the following morning. Usually I would have at least one bowel movement but this time I didn’t.

My weight and body composition were nearly the same at 186.9lbs and 9.9% fat. This consisted of 21lbs of fat, 161lbs of lean mass and 7.9lbs of bone. I had gained 2.5lbs of fat with 2lbs of it in my torso but I had also gained 3.2lbs of lean mass in my torso. The lean portion of this was likely due to stool content as previous testing comparing fasted and fed states had revealed similar changes in torso lean mass.

My metabolic results were finally showing nutritional ketosis with a respiratory exchange ratio of 0.75 indicated 84% fat burning at rest! My resting metabolic rate had bumped up to 2114kcal/day, now 428kcal and 25% higher than my pre-ketogenic level of 1686kcal/day two months prior. This may have been due to my increase in caloric intake in this second month, up to 4,602kcal from 4087kcal in the first month, 4093kcal in the three days before my baseline measurement and ~2,700 in the four months prior to that. My activity level had not changed dramatically in this time period although I was hiking a few miles every morning with newborn baby Zia starting January 29th, 2017 Overall, I was working out less than I had in the four months I spent eating ~2,700kcal. By the end of two months I was eating 509kcal more than when I started, and my metabolism had elevated by 428kcal.

As my stores of blood ketone test strips began to run low, I started measuring my blood glucose and seeing the correlation between it and my blood ketones. I found that if my blood glucose was below 90mg/dL, my blood beta-hydroxybutyrate was over 1mmol/L.

Hitting the Trail in Ketosis

My entire time on the ketogenic diet I remained free of commonly reported negative side effects. I had been diligent to maintain our fluid and electrolyte levels and we divided our food into 4-5 meals throughout the day. My sodium intake had consistently been >3,000mg per day and closer to 8,000mg on sweaty days when I was drinking 10+ liters of water.

I measured my fasted morning glucose every few days and my blood ketones once a week. My ketone levels ranged from 0.6 to 5.1mmol with an average of 1.8mmol/L and my glucose levels ranged from 77mg/dL to 105mg/dL with an average of 91mg/dL.

After a few days of packing and preparing resupply boxes we started our Appalachian Trail section hike northbound at Rockfish Gap on April 16th, 2017. I continued to experience consistent energy levels and had no negative side effects.

Shortly after starting our hike, news of the “family hiking with a baby” and the “dad who eats only fat” quickly spread and people greeted us on the trail as if we were old friends. My willingness to talk about my diet quickly validated my trail name “Keto.” The trail name Sherpa was suggested but it had already been given to Derrick Quirin who was hiking the entire trail that year with his wife Bekah “Kanga” and one-year-old baby Ellie “Roo.” We tried to give our own daughter Zia the trail name “Leech” on account of her sucking the milk and energy out of Jess but this name was repeatedly rejected, and Jess started going by “Leche” and Zia by “Chupaleche”, translated “The Milk Sucker.”

We both enjoyed the food we had packed but quickly found that the 10,000kcal/day I had packed for the family was far more than we needed. This was still less than the 13,396kcal estimate from the metabolic equivalent value for backpacking. Perhaps this was because the section we were hiking was less steep or our pace was slower because of stopping to nurse Zia.

We looked forward to the meals but rarely found ourselves hungry. I soon began sending things back or throwing them out. We consistently showed up at a resupply with a day or two of extra food. Much effort in food packing and a lot of good olive oil was wasted.

In the end, our pace on the trail was not limited by energy but by the aches and pains of adapting to hiking all day. We had planned to start out at 8 miles per day, but after a few days we were feeling antsy after arriving at camp at 3pm and picked it up to 13 miles per day.

Soon Jess’ knees were hurting and soon after our feet hit the cruel rocks of Pennsylvania. Feet and knees were ongoing issues, and Jess was hit hardest having had little time after giving birth to prepare her body. Frequent stopping to nurse our growing daughter also checked our pace and I did my best to quell my restless spirit and settle in and enjoy the ride. The various orthopedic challenges we experienced tested my on-trail physical therapy skills and we reached Dalton, MA sixty days and 707 miles later on June 14th, 2017. We had average 13 miles per day, 12 per day when including our six zero days with a median mileage of 14.

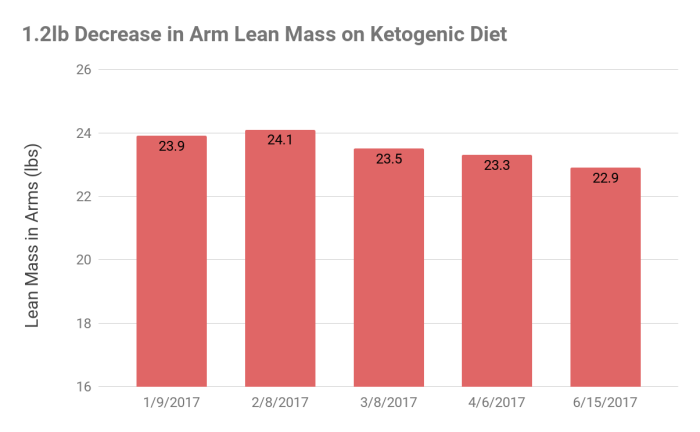

Once a week I did two sets each of the same four upper body strength exercises: 1) handstand pushups, 2) pullups; 3) pushups; and 4) body weight rows.

I did not do any specific lower body strength training.

I continued the ketogenic diet uninterrupted all the way through our Appalachian trail section hike and after, ending 143 days, nearly 5 months later on July 2nd, 2017.

On the way to a wedding in Minnesota I was scheduled to stopped by DEXAfit Minneapolis for my final measurements. We had missed an early morning connection flight thanks to me taking a nap by a self-playing piano in the Chicago O-Hare airport and as a result I walked into the lab the next afternoon having fasted for 23 hours vs the usual 15 hours.

My DEXA results showed I was nearly the same weight at 186.5lbs but my body composition had shifted in an unfavorable direction. There was no change in my arms, but my legs lost 1.2lbs of muscle and gained 1.3lbs of fat. Apparently that heavy pack hadn’t built any muscle after all. Despite this increase in fat in my legs, they looked leaner. This may have been due to an increase in intramuscular fat and decrease in superficial fat known to occur with long duration endurance training.

The largest and least trustworthy changes were seen in my torso which lost 4lbs of lean mass and gained 1.9lbs of fat compared to my last measurement. This torso lean change be attributed to the fact that my last measurement contained bowel contents and this measurement did not. But the fat mass increase was likely a true body fat increase.

When compared to my original, pre-ketogenic diet I had gained 6.4lbs of fat and lost 5.6lbs of lean mass with most of these changes occurring during my time on the Appalachian trail.

My respiratory exchange ratio was off the charts at 0.72, showed I was burning 95% fat at rest. However, my metabolism had slowed down by 11% to 1892kcal/day. This is similar to the basal metabolic rate drop of 10% that has been found in the research to accompany long duration aerobic exercise.

Summary

Despite diligent carbohydrate restriction I did not produce substantial ketones until I reduced my protein intake. During my entire time on the ketogenic diet I did not experience any negative side effects. My energy levels felt constant and I never had hiker hunger. I lost lean mass, and this can be attributed to a combination of glycogen loss seen in the first month of entering ketosis and true lean mass loss resulting from long distance hiking without sufficient strength training. I overpacked in food and ended up gaining fat along the trail. After rising initially, my metabolism dropped back down because of the hike.

Without having done a similar hike on a different diet I had nothing to compare the results to but overall, I was happy with the performance of the ketogenic diet. Still, I felt the pace we had set as a family was not testing the limits of my metabolic system and I was itching to get out on my own and push myself to the limit.

My Data

I started the ketogenic diet on February 5th, 2017 and our AT hike started on April 16th, 2017.

[1] A pound of pure fat would be 3,500kcal but fat on an actual human is stored as adipose tissue which is composed of 15% cellular water and protein and thus would only hold 2,975kcal. While this number is well established, there is debate as to whether a reduction of caloric intake of 3,500 will actually result in 1lb of fat loss because human rates of fat burning varies.